Leon Cooper

Leon Cooper | |

|---|---|

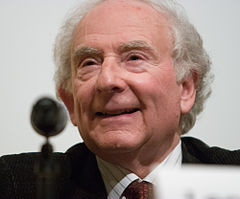

Cooper in 2007 | |

| Born | Leon N. Kupchik February 28, 1930 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | October 23, 2024 (aged 94) Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Columbia University (BA, MA, PhD) |

| Known for | Cooper pairs BCM theory BCS theory |

| Awards | John Jay Award (1985) Nobel Prize in Physics (1972) Comstock Prize in Physics (1968) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | Brown University |

| Thesis | Mu-Mesonic Atoms and the Electromagnetic Radius of the Nucleus (1954) |

| Doctoral advisor | Robert Serber |

Leon N. Cooper (né Kupchik; February 28, 1930 – October 23, 2024) was an American theoretical physicist and neuroscientist. He won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on superconductivity. Cooper developed the concept of Cooper pairs and collaborated with John Bardeen and John Robert Schrieffer to develop the BCS theory of conventional superconductivity.[1][2] In neuroscience, Cooper co-developed the BCM theory of synaptic plasticity.[3]

Biography

[edit]Childhood and education

[edit]Leon N. Kupchick was born in the Bronx, New York City on February 28, 1930.[4] His middle initial N. does not stand for anything, though some sources erroneously suggested his middle name was Neil.[4]

His father Irving Kupchik was from Belarus and moved to the United States after the Russian Revolution in 1917. His mother Anna (née Zola) Kupchik was from Poland; she died when Leon was seven.[4] His father later changed the family's surname from Kupchick to Cooper when he remarried.[4]

Leon attended the Bronx High School of Science, graduating in 1947[5][6] He then studied at Columbia University in nearby Upper Manhattan, receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1951.[7] He remained at Columbia for graduate school, obtaining a Master of Arts degree in 1953[7] and a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in 1954.[7][8] His PhD was on the subject of muonic atoms, with Robert Serber as his thesis advisor.[9][10]

Scientific career

[edit]Cooper spent one year as a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. New Jersey. He then taught at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign and Ohio State University before joining Brown University in 1958.[8] He would remain at Brown for the rest of his career.

Cooper founded Brown's Institute for Brain and Neural Systems in 1973, becoming its first director.[7] In 1974 he was appointed Professor of Science at Brown, an endowed chair funded by Thomas J. Watson Sr.[7] Cooper held visiting research positions at various institutions including the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and at CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Geneva, Switzerland.[citation needed]

Along with colleague Charles Elbaum, he founded the tech company Nestor in 1975, which sought commercial applications for artificial neural networks.[11][12] Nestor partnered with Intel to develop the Ni1000 neural network computer chip in 1994.[13]

Personal life

[edit]

Cooper first married Martha Kennedy, with whom he had two daughters.[4] In 1969, he married for a second time, to Kay Allard. [14] He died at his home in Providence, Rhode Island, on October 23, 2024, at the age of 94.[4]

Research

[edit]Superconductivity

[edit]

While Cooper was a postdoc in Princeton, he was approached by John Bardeen, a professor at the University of Illinois, and Bardeen's graduate student John Robert Schrieffer. Bardeen and Schrieffer were working on superconductivity, a topic which was new to Cooper but he agreed to collaborate with them. Superconductivity had been experimentally discovered in 1911, but there was no theoretical explanation for the phenomenon. Cooper moved to Illinois as a postdoc to work with Bardeen.

After a year of theoretical investigation, Cooper developed the idea of a quasiparticle composed of two bound electrons, now known as a Cooper pair. Cooper published his concept of Cooper pairs in Physical Review in September 1956.[4][15] The movement of Cooper pairs through a low-temperature metal would be almost unimpeded, producing a very low electrical resistance. After further development, Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer showed how this could produce superconductivity, publishing their theory in Physical Reviews in two papers during 1957.[4].[16][17] This theory became known as the BCS theory, after the authors' initials, and is widely accepted as the explanation for conventional superconductivity. Bardeen, Schrieffer and Cooper were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1972 for their theory.[4]

Neuroscience

[edit]After joining Brown University, Cooper became interested in neuroscience, particularly the process of learning. In 1982, Cooper and two doctoral students, Elie Bienenstock and Paul Munro, published their theory of synaptic plasticity in The Journal of Neuroscience.[4] They estimated the weakening and strengthening of synapses that could occur without saturation of the connections. As synapses saturate, electrical connections become less effective, thereby reducing the saturation. Connections therefore oscillate between saturation and unsaturation without reaching their limits. Their theory explained how the visual cortex works and how people learn to see. It became known as the BCM theory, after the authors' initials.[4]

Memberships and honors

[edit]- Fellow of the American Physical Society[citation needed]

- Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[citation needed]

- Member of the National Academy of Sciences[citation needed]

- Member of the American Philosophical Society[citation needed]

- Member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science[citation needed]

- Associate member of the Neuroscience Research Program[citation needed]

- Research fellow of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (1959–1966)[citation needed]

- Fellow of the Guggenheim Institute (1965–66)[citation needed]

- Nobel Prize Recipient for Physics (1972)[7]

- Co-winner (with Dr. Schrieffer) of the Comstock Prize in Physics of the National Academy of Sciences (1968)[18]

- Received the Award of Excellence, Graduate Faculties Alumni of Columbia University[citation needed]

- Received the Descartes Medal, Academie de Paris, Université René Descartes.[citation needed]

- Received the John Jay Award of Columbia College (1985)[7]

- Recipient of seven honorary doctorates[7]

Publications

[edit]Cooper was the author of Science and Human Experience – a collection of essays, including previously unpublished material, on issues such as consciousness and the structure of space. (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Cooper also wrote an unconventional liberal-arts physics textbook, originally An Introduction to the Meaning and Structure of Physics (Harper and Row, 1968)[19] and still in print in a somewhat condensed form as Physics: Structure and Meaning (Lebanon: New Hampshire, University Press of New England, 1992).

- Cooper, L. N. & J. Rainwater. "Theory of Multiple Coulomb Scattering from Extended Nuclei", Nevis Cyclotron Laboratories at Columbia University, Office of Naval Research (ONR), United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission), (August 1954).

- Cooper, Leon N. (1956). "Bound Electron Pairs in a Degenerate Fermi Gas". Physical Review. 104 (4): 1189–1190. Bibcode:1956PhRv..104.1189C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.104.1189.

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L. N.; Schrieffer, J. R. (1957). "Microscopic Theory of Superconductivity". Physical Review. 106 (1): 162–164. Bibcode:1957PhRv..106..162B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.106.162.

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L. N.; Schrieffer, J. R. (1957). "Theory of Superconductivity". Physical Review. 108 (5): 1175–1204. Bibcode:1957PhRv..108.1175B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.108.1175.

- Cooper, L. N., Lee, H. J., Schwartz, B. B. & W. Silvert. "Theory of the Knight Shift and Flux Quantization in Superconductors", Brown University, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission), (May 1962).

- Cooper, L. N. & Feldman, D. "BCS: 50 years", World Scientific Publishing Co., (November 2010).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Superconductivity". CERN official website. CERN. July 21, 2023.

- ^ Weinberg, Steven (February 2008). "From BSC to the LHC". CERN Courier. 48 (1): 17–21.

- ^ Bienenstock, Elie (1982). "Theory for the development of neuron selectivity: orientation specificity and binocular interaction in visual cortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 2 (1): 32–48. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-01-00032.1982. PMC 6564292. PMID 7054394.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k McClain, Dylan Loeb (October 25, 2024). "Leon Cooper Dies at 94; Nobelist Unlocked Secrets of Superconductivity". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ "Bronx Science Honored as Historic Physics Site by the American Physical Society". bxscience.edu. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ MacDonald, Kerri (October 15, 2010). "A Nobel Laureate Returns Home to Bronx Science". The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Leon Cooper". research.brown.edu. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ a b Vanderkam, Laura (July 15, 2008). "From Biology to Physics and Back Again: Leon Cooper". Scientific American. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ "Cooper, Leon N. (Leon Neil), 1930-". history.aip.org. Retrieved November 1, 2024.

- ^ Leon Cooper at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ Johnson, Colin (October 17, 1988). "Neural Network Startups Proliferate Across The U.S." The Scientist. 2 (19). Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ Garson, G. David (September 28, 1998). Neural Networks: An Introductory Guide for Social Scientists. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-7619-5730-0.

- ^ "Nestor's neural chip destiny now in its own hands". Tech Monitor. April 14, 1994. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ Carey, Charles W. (2014). American Scientists. Infobase Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4381-0807-0.

- ^ Cooper, Leon (November 1956). "Bound Electron Pairs in a Degenerate Fermi Gas". Physical Review. 104 (4): 1189–1190. Bibcode:1956PhRv..104.1189C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.104.1189. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L. N.; Schrieffer, J. R. (April 1957). "Microscopic Theory of Superconductivity". Physical Review. 106 (1): 162–164. Bibcode:1957PhRv..106..162B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.106.162.

- ^ Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L. N.; Schrieffer, J. R. (December 1957). "Theory of Superconductivity". Physical Review. 108 (5): 1175–1204. Bibcode:1957PhRv..108.1175B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.108.1175.

- ^ "Comstock Prize in Physics". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010.

- ^ Cushing, James T. (1978). "Review of An Introduction to the Meaning and Structure of Physics by Leon N. Cooper". American Journal of Physics. 46 (1): 114–115. Bibcode:1978AmJPh..46..114C. doi:10.1119/1.11116.

External links

[edit]- Leon Cooper on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1972 Microscopic Quantum Interference Effects in the Theory of Superconductivity

- Brown University researcher profile

- Brown University Physics Department profile

- Critical Review evaluations[permanent dead link] of Professor Cooper

- Leon Cooper at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- 1930 births

- 2024 deaths

- 20th-century American physicists

- 21st-century American physicists

- American Nobel laureates

- American people of Belarusian-Jewish descent

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- Brown University faculty

- Columbia College (New York) alumni

- Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Fellows of the American Physical Society

- Institute for Advanced Study visiting scholars

- Jewish American physicists

- Jewish neuroscientists

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- Nobel laureates in Physics

- People associated with CERN

- Scientists from the Bronx

- Superconductivity

- The Bronx High School of Science alumni